In the 1900s Britain’s tropical empire was patched together and lacked conformity. In British Guiana the currency was dollars and cents and law was based on Dutch ideas; in eastern Africa the rupee and Indian law were used. In Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe and Zambia) daily affairs were largely in the hands of the British South Africa Company but there – and elsewhere, notably Uganda – local rulers had direct links with the Colonial Office in London, established by contracts and agreements which, as white settlers sought domination, were treated with great respect by the Africans. By keeping up the direct connection with Britain, the colonialists could be thwarted.

The Lozi people of what became western Zambia, and was then called Barotseland, were pulled into the sphere of the British South Africa Company in mid-1890. The various traditional leaders and groups united under Lewanika, who represented a semi-independent African kingdom and so was invited to attend the coronation of Queen Victoria’s son and heir, Edward VII, in 1902. The visit was extended as the British monarch was ill and his coronation was postponed for weeks.

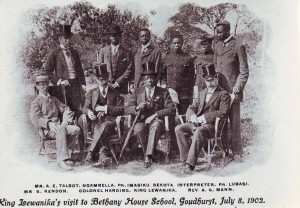

Something of the story is to be found in Colin Harding, Far Bugles (1933). Harding, an administrator in Barotseland from 1899, accompanied Lewanika and his group from Cape Town to England. They visited Yeovil, Sherborne (Harding came from nearby), Reading, and Goudhurst in rural Kent where two of Lewanika’s sons were at Bethany House School. The above photograph was issued as a postcard (my thanks to Skene Catling).

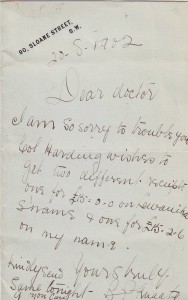

The group’s secretary wrote requesting £30-2s-6d of receipts from a London doctor – see above letter.

Sekota (as in the postcard) or Sikota Kwandu was interviewed and that was published in the Northern Rhodesian Journal in 1953, another coronation year. He recalled visiting Sheffield, Manchester, Glasgow and Edinburgh. A successor to Lewanika, Yeta, worked “indefatigably to proclaim special royal status” and was invited to the coronation of Edward’s grandson in 1937 (and it was detailed in his secretary Godwin Mbikusita’s Yeta III’s Visit to England. Lusaka: 1940).

Although Africans worked as crew on ships, appeared on stage and at exhibitions, they also attended universities and medical schools, private schools such as Bethany House School and Epsom College, wrote books, visited rural locations, and observed the activities of whites. That a group from the then-somewhat remote Barotseland saw so much in Britain in 1902 suggests that further investigation could expose more individuals.

Further reading: Jeffrey Green, Black Edwardians: Black People in Britain 1901-1914 London: Frank Cass, 1998; Terence Ranger, “The Invention of Tradition in Colonial Africa” in Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (eds), The Invention of Tradition Cambridge University Press, 1983 and often thereafter; and Gwyn Prins, “The Battle for Control of the Camera in Late-nineteenth-century Western Zambia” in Elizabeth Edwards (ed), Anthropology & Photography 1860-1920 New Haven CT, Yale University Press, 1992, pp 218-224. Detailed accounts of Africans in Britain a century ago include: Brian Willan, Sol Plaatje: South African Nationalist 1876-1932 London: Heinemann, 1984; Neil Parsons, King Khama, Emperor Joe, and the Great White Queen: Victorian Britain through African Eyes University of Chicago Press, 1998; and Ben Shephard, Kitty and the Prince London: Profile Books, 2003.

In late 2014 an investigation into Colin Harding confirmed his Yeovil, Somerset links for he was buried in Montacute in early 1939. Author of three books – In Remotest Barotseland of 1904 and Frontier Patrols (1937) have been reissued on a print on demand system – and awarded the colonial CMG and a military DSO (1917), he seems to have been born in 1863. Lt-Col. Edwin Colin Harding died aged 75 in a London nursing home on 3 January 1939. Probate documents indicate his home was Gaye House, Highmoor Road in Caversham. Probate was issued to his sole child, Diana Colin Nisbet wife of Brian Callaway Nisbet. The estate was valued at £4511. Her son John was born in 1942. The Times had a brief note on 4 January page 10: ‘who served many years in Africa and was a Rhodesian pioneer’ and a longer notice on page 12. A younger brother William Hallett Harding born 1866 died in Africa in 1901. The website “History of Monze” has details.

LEAVE A RESPONSE IN THE ‘LEAVE A REPLY’ BOX AT THE END OF THIS PAGE.