We’ve been thinking of ways to keep the blog ‘alive’, but without giving too much away in terms of photos and material. The book will try to ‘make the crag the star’ so what better way to blog about it than to focus on the crags. So, each blog post for the next while will be themed around the regions and crags upon which the book is focused, with stories, history and pictures about the climbing to be had. It would be great if you’re reading the blog and you’ve had a memorable experience on the crag in question if you can throw your hat in the ring and tell us some more!

We’ve been thinking of ways to keep the blog ‘alive’, but without giving too much away in terms of photos and material. The book will try to ‘make the crag the star’ so what better way to blog about it than to focus on the crags. So, each blog post for the next while will be themed around the regions and crags upon which the book is focused, with stories, history and pictures about the climbing to be had. It would be great if you’re reading the blog and you’ve had a memorable experience on the crag in question if you can throw your hat in the ring and tell us some more!

First off it’s Arran, and the choice words of a couple of our most stalwart of forefathers…

‘…we left our sacks and started off in rubbers for the climb, aiming at the foot of a prominent S-shaped crack, which is the main feature of the lower tier of the cliff. It is a formidable crack, soon approaching the vertical… the final upward move on onto the slab on the right was very awkward and exposed. We were now about the centre of the steep lower cliff, in a comfortable and agreeable situtation, with a splendid view over the nearer hills across the Firth of Clyde, but with no answer to the urgent question: where next? Just above George (Collie) was a steep slab, split by a crack and ending under a slightly overhanging wall, about eight to ten feet high. The crack narrowed and split the wall, forking like a letter Y below the top. It was not a very high wall, but the crack was too narrow for anything but sideways wedging of the toes and there was no guarantee of postive holds above the Y…’

J H B Bell on a May 1945 attempt on Cir Mhor’s South Ridge

‘I felt released in a world lively and free, which awakened in me the illusion of watching the spin of the earth and its flight through interstellar space… from the lofty pass I watched the sweep of the earth through a chartless universe with the added sense of a majestic rhythm of movement, which may be best likened to the greatness of rhythm in a Beethoven symphony. The illusion lasted half a minute and disappeared with the arrival of Mackinnon.’

W.H. Murray on a 1939 ascent of B2C Rib on Cir Mhor’s North Face

1892 was an interesting year in Scotland: weather was reported as inclement, influenza was spreading fast and ‘Buffalo’ Bill Cody had set up his wild west circus in Glasgow. On the 2nd January, he lost one of his Lakota Indian workers (‘Charging Thunder’) to Barlinnie prison on an assault charge aggravated by spiked lemonade in a Glasgow pub. The Calcutta Cup (made from melted down colonial rupees), was the big sporting occasion of the year, with England humping Scotland 5-0. Rock climbing was also a new oddity.

1892 was an interesting year in Scotland: weather was reported as inclement, influenza was spreading fast and ‘Buffalo’ Bill Cody had set up his wild west circus in Glasgow. On the 2nd January, he lost one of his Lakota Indian workers (‘Charging Thunder’) to Barlinnie prison on an assault charge aggravated by spiked lemonade in a Glasgow pub. The Calcutta Cup (made from melted down colonial rupees), was the big sporting occasion of the year, with England humping Scotland 5-0. Rock climbing was also a new oddity.

Archibald Geikie had just published his updated geology map of Scotland, nestling neatly into the tweed hip pockets of a nascent but vigorous Scottish Mountaineering Club, who visited the island of Arran in January 1892 to attempt the A’Chir ridge several months after William Wilson Naismith scratched his nails up the formidable North Face of Cir Mor. The granite of Arran, and its unfair rumours of rotten rock and vegetation, was attracting mountaineers before even the great Tower Ridge of Ben Nevis existed as the best ridge-climb in Scotland. This particular January was tumultuous; heavy gales had lashed the Firth of Clyde the week before the Arran meet and it was reported as a ‘somewhat boisterous voyage to Brodick’. So began the development of Arran rock climbing.

Archibald Geikie had just published his updated geology map of Scotland, nestling neatly into the tweed hip pockets of a nascent but vigorous Scottish Mountaineering Club, who visited the island of Arran in January 1892 to attempt the A’Chir ridge several months after William Wilson Naismith scratched his nails up the formidable North Face of Cir Mor. The granite of Arran, and its unfair rumours of rotten rock and vegetation, was attracting mountaineers before even the great Tower Ridge of Ben Nevis existed as the best ridge-climb in Scotland. This particular January was tumultuous; heavy gales had lashed the Firth of Clyde the week before the Arran meet and it was reported as a ‘somewhat boisterous voyage to Brodick’. So began the development of Arran rock climbing.

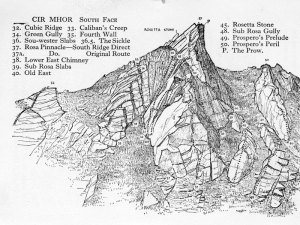

Once the ridges were linked in the great horseshoe surrounding Goatfell, the chimneys and gullies began to attract attention, with the vegetated North East face of Cir Mhor oddly drawing the attention of technical climbers like Bell and Green who climbed the under-rated but exceptional (for the time) B2C Rib (V Diff) in 1895. The sparkling slabs were obviously ignored as impossible by the hobnailed feet of the day and the blank armour of the south face of Cir Mhor (our modern clean slabs of Insertion etc.) was seen as terra incognita.

In 1936 Arran regained its pride when the distinctive South Ridge was conquered, with the now-classic direct line resolved five years later by J.F. Hamilton to give Scotland one of its most attractive long climbs. In 1938 the East Face of the Rosa Pinnacle saw the significant first HVS ascent on the island, with K. Barber and A.S.Pigott climbing Easter Route, which tackles the intimidating steep chimney lines of this high face. This was originally given Severe, mainly because limits were still fuzzy on the grading scale, but it is very close to the 1957 HVS of The Sickle by Ashford and Burke, when Extreme grades were about to become a necessity.

In 1936 Arran regained its pride when the distinctive South Ridge was conquered, with the now-classic direct line resolved five years later by J.F. Hamilton to give Scotland one of its most attractive long climbs. In 1938 the East Face of the Rosa Pinnacle saw the significant first HVS ascent on the island, with K. Barber and A.S.Pigott climbing Easter Route, which tackles the intimidating steep chimney lines of this high face. This was originally given Severe, mainly because limits were still fuzzy on the grading scale, but it is very close to the 1957 HVS of The Sickle by Ashford and Burke, when Extreme grades were about to become a necessity.

The 1940’s was obviously a decade of privation and priorities, but nevertheless, a local Admiralty party of climbers led mainly by Curtis, Moneypenny and Townend (not lawyers!), developed the other big faces such as Meadow Face and the South Face of Cir Mhor (including Sou’wester Slabs) when not busy chasing submarines from an engineering base on the Clyde. They also discovered the other classic ridges on the island such as Pagoda Ridge in Coire Daingean.

In 1958 the first climbing guide to Arran was published as a slim 84 paged illustrated booklet by J.M. Johnstone, which signalled the end of the classic period on Arran, when all things vegetated and thrutchy would be forgotten. From here on in, the blankness of granite would be explored with longer ropes, rubber-soled PA’s and more technical protection equipment.

In 1958 the first climbing guide to Arran was published as a slim 84 paged illustrated booklet by J.M. Johnstone, which signalled the end of the classic period on Arran, when all things vegetated and thrutchy would be forgotten. From here on in, the blankness of granite would be explored with longer ropes, rubber-soled PA’s and more technical protection equipment.

The first E1 was actually a mistaken ascent, with McKelvie and Sim climbing Minotaur on the East Face of the Rosa Pinnacle, somehow thinking it was the easier route Labyrinth. Probably the most significant route of the 60’s was the ascent of the Meadow Face’s alpine-like sweep when Bill Skidmore and Bob Richardson succeeded on The Rake, a long and complex E2 in modern terms. The Meadow Face also saw ascents of Brachistochone E1 and Bogle E2 in the 60’s. Andrew Maxfield was active at this time, climbing E2’s such as Klepht on the The Bastion at Cioch na h’Oighe. 1969 saw the first ascent of the esoteric Voodoo Chile on the Full Meed Tower by young hardcore climber Graham Little. 1969 also saw the team of Rab Carrington and Ian Fulton rip up the grades with a first ascent of The Curver and the desperate friction problem of Insertion on the lower slabs of Cir Mhor, given E3 and the first serious slab climb on the island.

The 1970’s started from a new base-line in terms of standards on Arran, with Bill Wallace updating the Arran Guide to include the new technical routes, but still no sign of the extreme grade despite a few notable anachronisms! The 70’s and 80’s and the 90’s were essentially a grade chase, with the most extreme and steepest lines being sought often at the expense of the concept of a ‘route’, with big pitches such as Insertion Direct E5 and West Point E4 (1975, Howett & Charlton), Abraxas free (1985), Vanishing Point E4 (1985 Craig MacAdam), Token Gesture E5 by Cuthbertson & Howett (1985) and so on past the Millenium into the new ‘headpoint’ era, with the most significant route being John Dunne’s 2001 three pitch The Great Escape E8 on Cioch na h’Oighe, unwittingly repeated by Dave MacLeod a few days later.

Climbing hard for its own sake in these decades generally overtook the idea of simply conquering a face from bottom to top via ‘the easiest line’ and hard single pitches were being sought on the steep island faces of the unpronounceable Cuithe Mheadhonach, or on The Bastion, such as the siege of Abraxas E4 by Graham Little in 1980. However, some stuck to the older themes and completed some big multi-pitch extremes, most significantly the gigantic Brobdingnag E2 on the Meadow Face by Ian Duckworth and party in 1975. The most significant classic modern route was the 1981 three-pitch exposure of Skydiver on the Rosa Pinnacle (an aptly named E3 with a hard second groove pitch seeing frequent falls) aided by Graham Little and Colin Ritchie, which was freed shortly after in 1984 by Andy Nisbet and Colin MacLean. This route stands as one of the most testing extreme multi-pitches on Arran and testament to the steep technical secrets of Arran granite.

August 4, 2013 at 8:18 am |

I’m impressed, I have to admit. Rarely do I come across a blog that’s both educative and entertaining, and without a doubt, you’ve hit the nail on the head. The problem is something too few people are speaking intelligently about. Now i’m very happy that I found this during my search for something concerning this.